Instructors

Dr. Karla Saldana Ochoa

Dr. Riccardo Villa

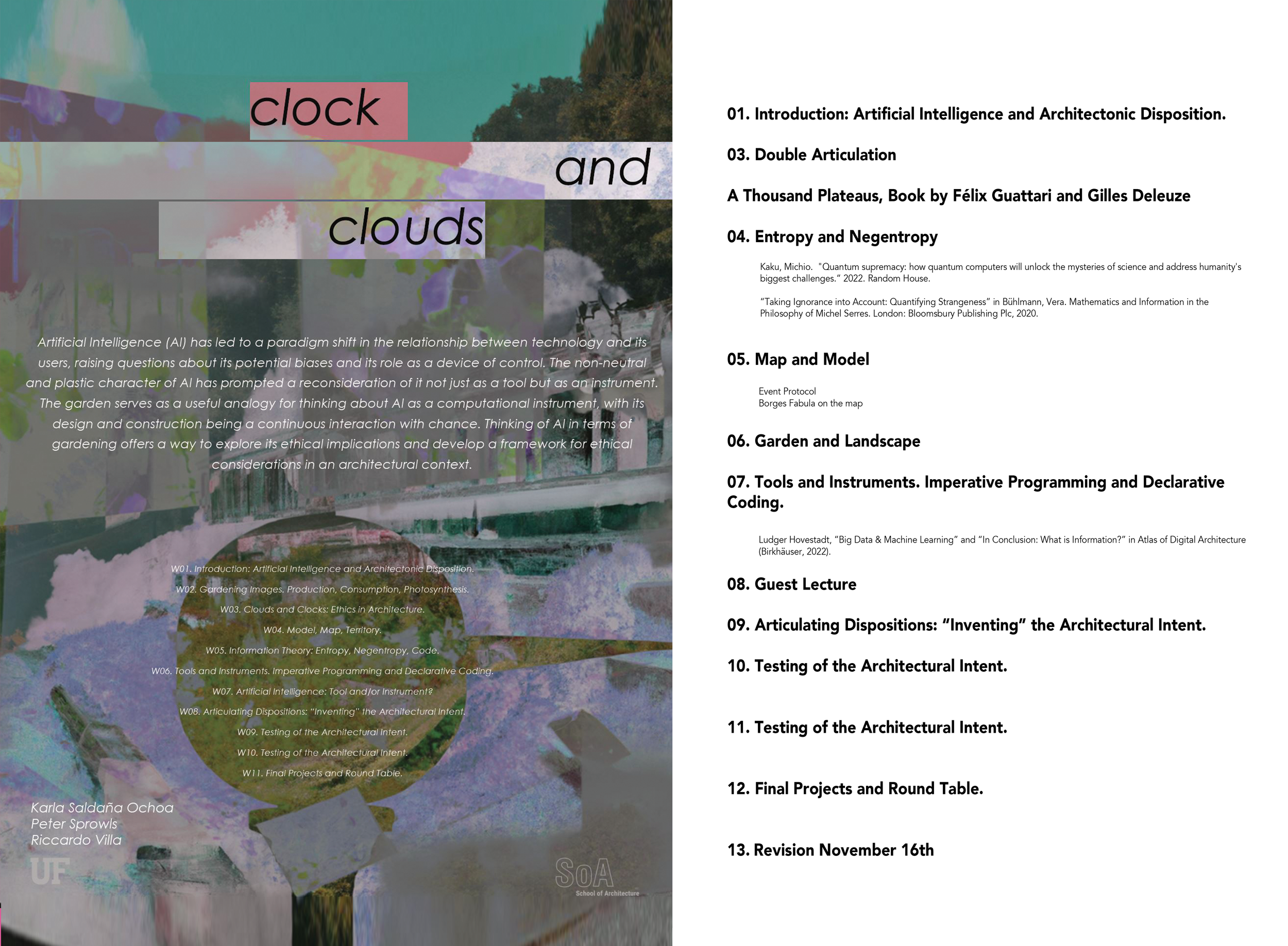

Artificial Intelligence can be considered as both the outcome and the reason for a paradigm shift. Amongst the changes introduced by A.I., there is undoubtedly a novel relationship with technology: for a long time, technical tools have been considered “neutral” vis-à-vis their users—to the extent that precisely the technical nature of modern science long stood as a warranty of its objective character—and yet, after A.I., it seems almost impossible to discuss technology without mentioning what kind of bias it might convey. Such an issue clashes with the claim of fairness typical of cybernetic systems or of any process in which the so-called “human element” (Brillouin, 1956) does not play any decisional role. Furthermore, A.I. seems to expose society to the danger of enhancement and totalisation of such biases whenever it becomes a device of control—through the encoding, within A.I., of a determinate alignment. And yet, at the same time, A.I. seems to be extremely useful, a “tool” able to perform tasks at another scale, incommensurable to one of “traditional” computational tools. Compared to the latter, A.I. is faster and more powerful. Even more importantly, AI recently has moved from a rule-based or parametric model to one that is not subject to or designed by preconceptions of the world but instead is data-driven and malleable, in which order is conveyed “plastically,” not through a rigid scheme provided by a set of positive rules.

The non-neutrality and the plastic character of A.I. urge us to rethink it not just as a tool but as an instrument. A tool is conceived for a particular use. Instruments can be played, and yet their playfulness does not necessarily exclude their potential usefulness. But first and foremost, instruments are about objects as much as subjects: they do not affect just their ‘products’ but their users, too. Such differences between instruments and tools can be illustrated by the fact that the moment one plays the piano becomes a pianist. Still, whenever one uses a tool such as a hammer, she is not perceived as a ‘hammerist’. Within instruments, subjects and objects entertain a two-way exchange, a form of communication.

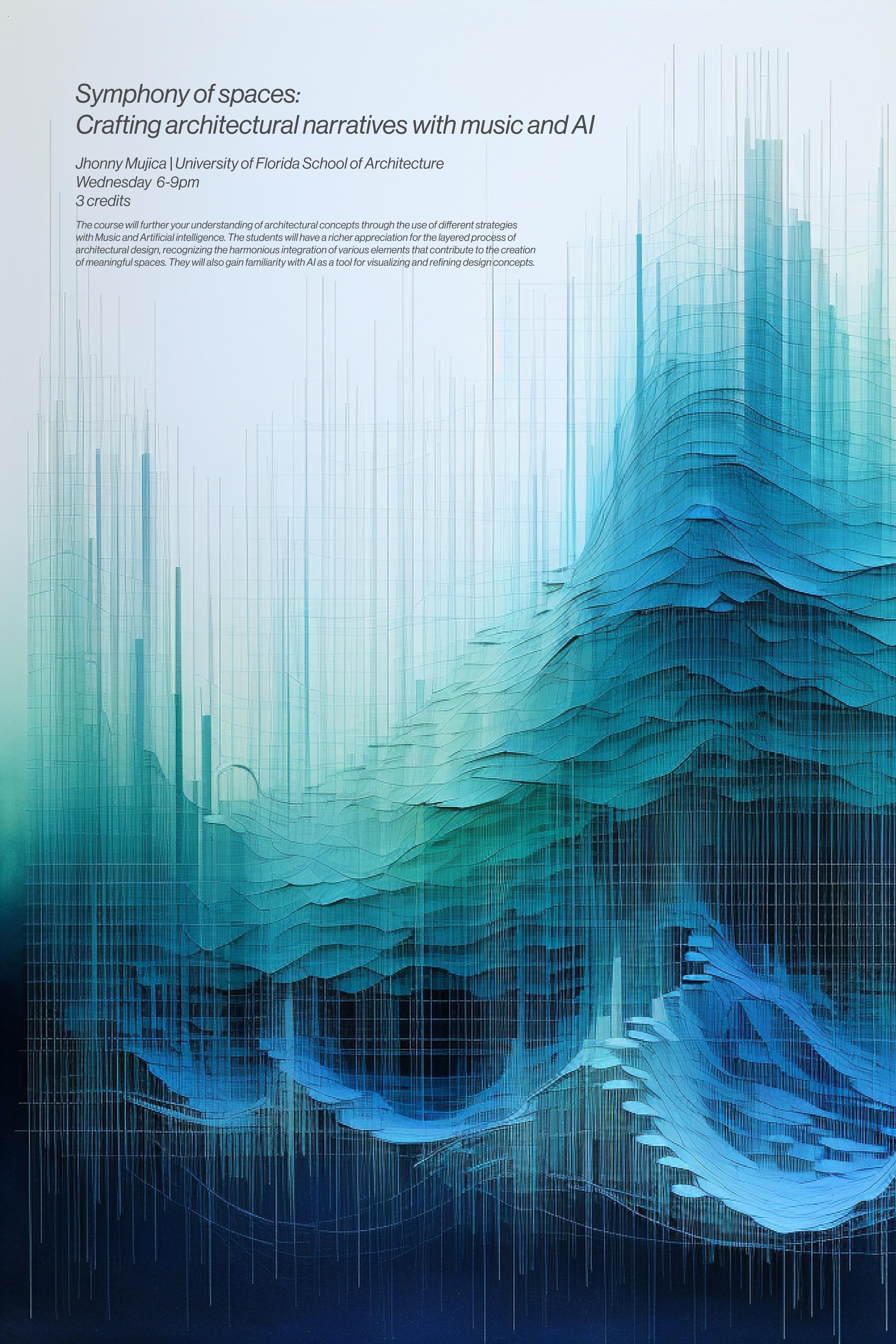

Such an instrumental nature of A.I. can be conceived, in architectonic terms, through the figure of the garden. The garden is a locus of encounter and of communication between what is traditionally thought of in terms of opposites: it is both natural and artificial, private and public. Most importantly, though, the garden effaces antinomies between subjects and objects, as it deals both with the subjective picture of the landscape and the objective one of the environments. In such an encounter, subjective biases can be plastically and objectively shaped as architectural intents.

Moreover, the garden offers a model of thinking plasticity in architectural terms: its design is not an execution of a pre-existing design, but its design and execution immanently overlap; its construction is a continuous contract with chance, exposed to the ‘randomness’ of the weather. Through such a model, A.I. can be rethought as a computational instrument that does not deal with data in terms of pre-determinacy. Still, in a ‘quantum’ way—it operates in between the ‘cloud’ of data and the ‘clock’ of computer hardware (Popper, 1979). Presenting a locus that escapes both mechanistic determinacy and total contingency, thinking of A.I. in terms of “gardening” can be a fruitful way to introduce the question of ethics and develop it in an architectonic way.

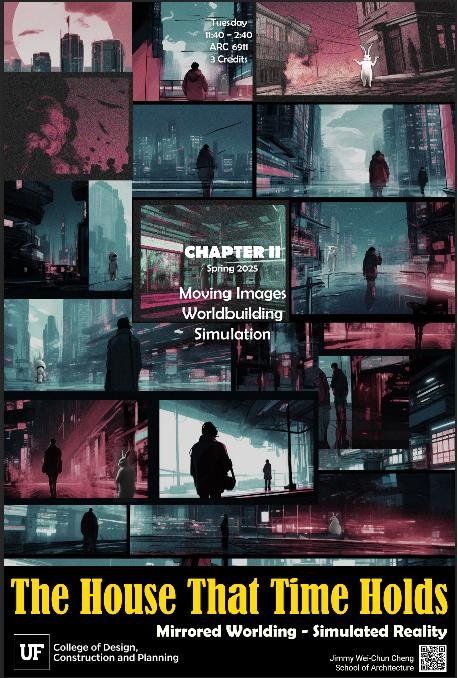

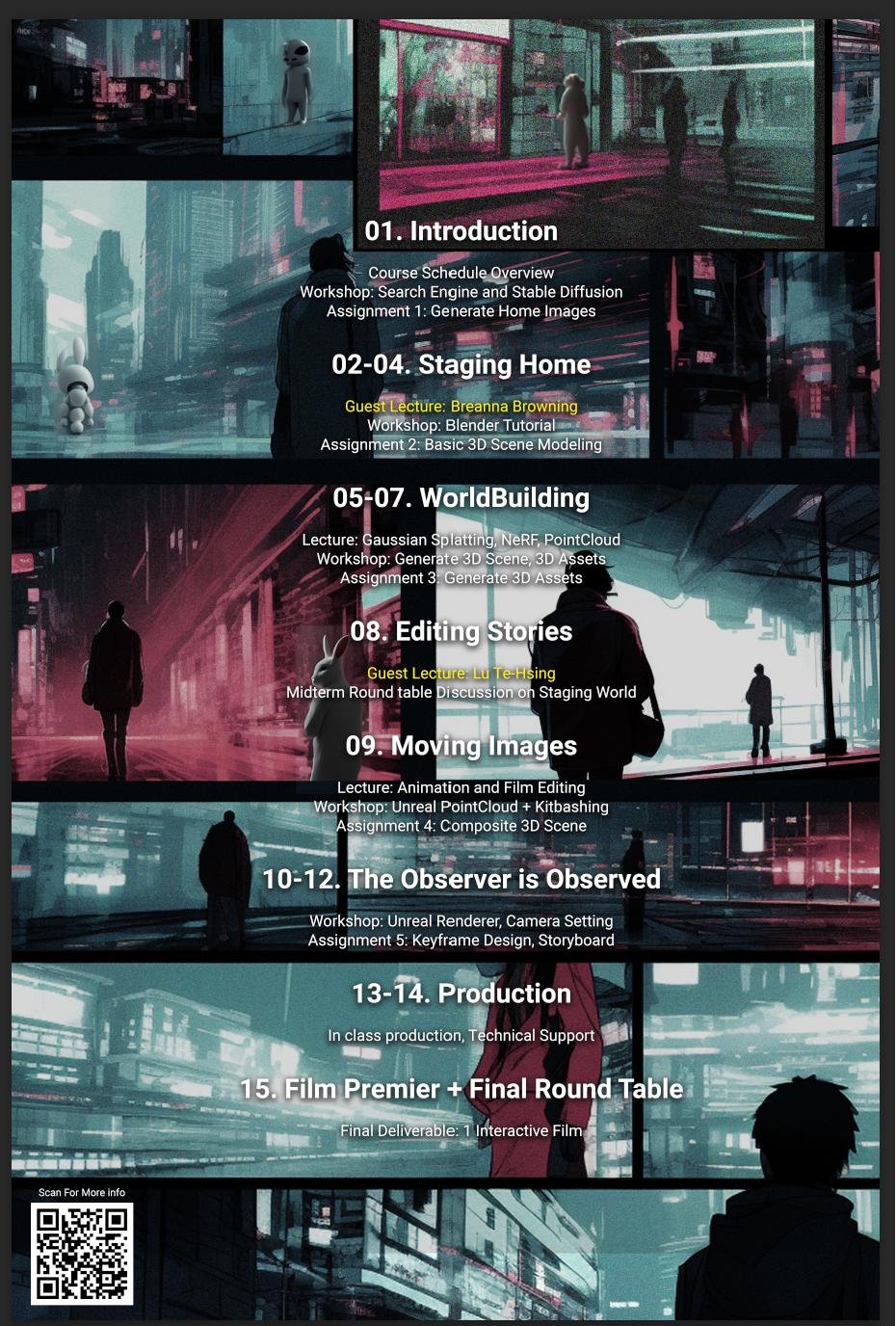

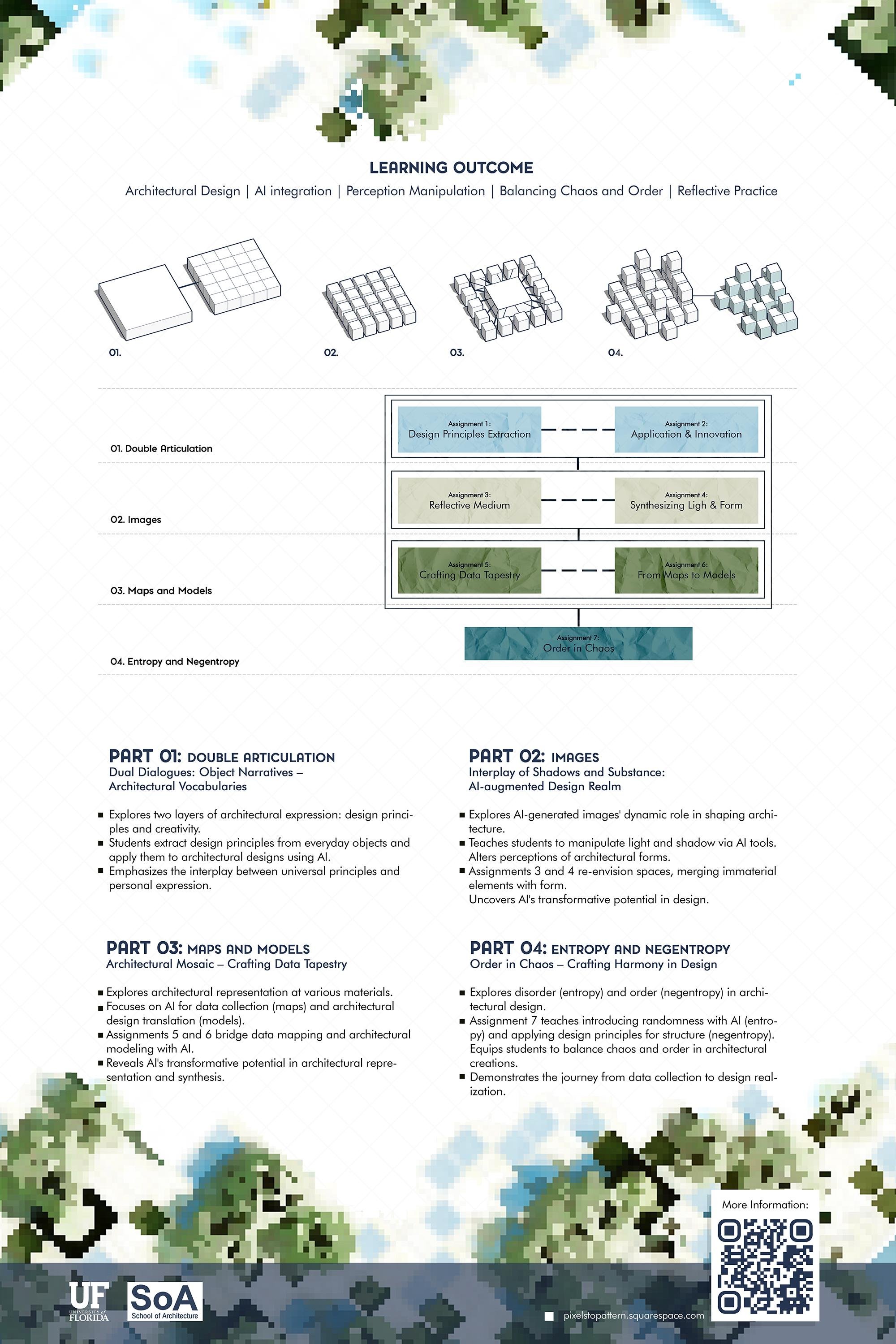

Sample of Student Work